Dormant

Oaks and tulips in January

A very stuffed caterpillar, dangling in silk

A lone set of instructions for blue irises, or cystic fibrosis

An octopus, the color and texture of the reef

A warrior, before the battles find her

A land mine on a road less traveled

Earth’s mantle, melting, bubbling, losing density

Carbon, asleep in a permafrost bed

Stranded bipeds, Curious and Perseverant

Waiting

To wreak transformations terrible and beautiful

To offer the latest proof

Of change

As the only constant.

When Your Garden Tends You

By March, the weather in Virginia was on its way to pleasant. Optimistic catkins and leaf buds were emerging on the trees and perennials. The gawdy daffodils, always looking overdressed for the occasion, were in full bloom. The pink camellias were opening. The tulip sheaths were asserting themselves skyward.

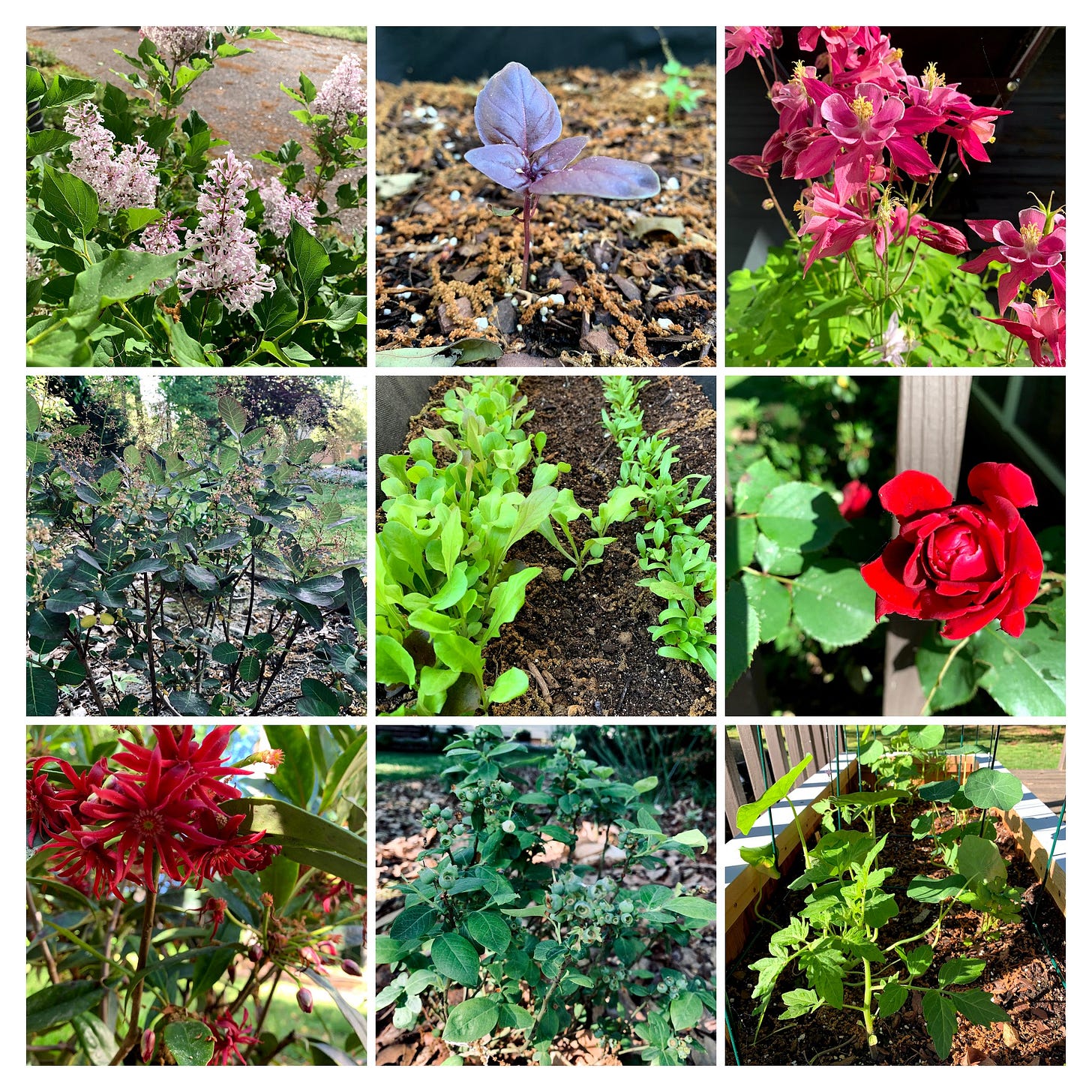

I was more than ready for rebirth. In the fall, I’d planted another viburnum, a smoke tree, two pentsemons, a spirea bush, and the bulbs for those tulips. Now, I added a lenten rose, five varieties of blueberry, and some lavender for the bees and butterflies. I ordered big new planters for the deck, a small mountain of good topsoil, and thousands of seeds for flowers, herbs, and tomatoes.

I started to hear a soft ringing in my left ear. When it persisted for a couple of days, I Googled “tinnitus” and stopped taking ibuprofen, like all the websites suggested. I followed the universal advice to keep exercising and sleep responsibly. The ringing got louder.

Figuring this strange new ailment could leave as quickly as it arrived, I tried to ignore it, spending hours outside. I painted the new cedar planters a pale blue. I cut English ivy off the hefty trunks of sycamores and sweet gum trees. I sheet-mulched the creeping, always creeping, liriope with the cardboard we’d saved from months of having everything we bought shipped to us. I hunted and destroyed Chinese privet and left the darker, glossier Japanese type alone.

By the time I went to my next oncology appointment, the ringing had only gotten angrier over two weeks. Madness was setting in.

“Your cancer response is awesome!” I heard my oncologist say over the dial-up modem in my brain. “None of the tumors are visible anymore on your scans. You’re not going to need any more treatment.”

“Wow, that’s so great!” I said, unsure now how much longer I could endure being alive.

Figuring that my T cells were still overzealous from cancer treatment and attacking my auditory system, the doctor prescribed a high dose of corticosteroids. I took the pills and waited for any sign that the ringing would subside. My heart raced, a steroid side effect. My brain was foggy and plain exhausted from the loud, non-stop noise. Promising my family that we would celebrate the good news about my longevity later, I crawled into bed and watched David Attenborough’s Our Planet series on Netflix from beginning to end, because it required nothing from me except awe at the grand scale of life on earth. It was a relief to feel insignificant.

The ringing continued and worsened in the subsequent days. I started to lose hope.

Sentient existence became almost intolerable at times. Doctors couldn’t offer me any additional explanations or remedies. One specialist’s website advised tinnitus sufferers to simply convince ourselves to accept a constant freight train sound in your head as “part of you.” I dreaded waking up to have to spend time in my own mind. My cognitive agility was noticeably weighed down by the never-ending drone my brain had created. Around this time, news outlets reported that a wealthy businessman had committed suicide after complaining of severe and prolonged tinnitus caused by COVID-19. My vision fluctuated, as it had since I started cancer treatment; an audiology exam showed that now I had some hearing loss, too. A small number of patients who receive cancer treatment like mine experience total vision or hearing loss. I tried not to be afraid, but I started to cherish my everyday sights and sounds as if they might soon be lost to me. The specific shade of green and leaf outline adopted by this plant species versus that one. The expression on my child’s face across the room. The individualized rhythm of each family member’s descent down the stairs. Laughter.

I took a leave of absence from work and spent sleepless nights in the guest room. Into the early morning hours, I watched Our Planet again, and then again. With my cognition impaired, I found myself strongly relating to the many creatures, large and small, who have no choice but to share the Earth with us. How few achievements are required of them, and how beautiful and magnificent their lives are nevertheless. Their imperatives are to eat, drink, rest, care for their children, and try to avoid danger. In the wild, these basic needs are all-consuming, and meeting them is enough. Fighting through the haze of tinnitus and steroids, I followed the lead of our fellow animals and relearned how to focus on my own essentials hour by hour: keep my body nourished, hydrated, and rested. Spend time with my kids. Stay vigilant for dangers to our family, which are now mostly products of our civilization instead of natural threats.

Whenever I could muster the energy, I pushed myself outdoors. As March turned to April, I demolished an old compost heap in our little forest and, in the rich soil underneath it, I sowed shade-tolerant wildflower seeds and planted a rhododendron, a plum yew, and two kinds of lorapetalum. I gathered and chipped piles of downed or pruned wood to make mulch. I threw nitrogen-fixing clover seeds all over the ailing lawn. I pulled up tufts of invasive garlic mustard and wild grapevines. I installed an anise tree to combat erosion in a spot where puddles form in the rain. One botanical Google search and Instagram follow led to another. The land and its wild inhabitants expected nothing from me; they just accepted whatever I happened to offer, as they always have.

I learned that soil is healthiest when it hosts a thriving, biodiverse underground ecosystem undisturbed by digging, and that last year’s untidy yard debris is the early-spring nursery for beneficial insects. I celebrated when the redbud branches turned pink and the new-wood hydrangeas leafed out. I prayed over the lantanas, hosts to last summer’s butterflies and hummingbirds, still showing no new growth after I’d overzealously cut them back in the winter and then, adding insult to injury, transplanted them for aesthetic reasons that seemed critical at the time. Over two weeks, I acclimated the seedlings we’d started indoors to the harsh elements, and I vigilantly tracked the overnight temperatures to guess when it was safe to put them in the planters for good. I cut down nets of Japanese honeysuckle and thorny flying dragon suffocating young redcedar trees. I watched carpenter bees visiting purple deadnettle and violets and, later, bursts of phlox and azalea blooms. I lingered at the lilacs, wishing their fragrance would just follow me around everywhere. I sighed in weary exasperation as oak pollen turned everything yellow.

For whatever reason, I started to hear less of a freight train, loud modem, or endless tuning fork in my ear, and more just an overactive computer fan or HVAC system, or maybe a phantom metal shop a block away. I started to wean off steroids, too, contracting my mood variability back toward my familiar, narrow “no drama” range. When meeting basic needs every day seemed mostly doable, I asked myself hour by hour what else I could still do that felt like me. Occasionally the answer was “nothing”; but usually it wasn’t. I taught myself to read over the din. I accepted that exercise would intensify the volume temporarily but would also make me feel strong and healthy. I played games, watched TV, and cooked dinners with my family. I helped my daughter celebrate a joyful thirteenth birthday, despite everything. Eventually, I put on music and danced and sang along.

It’s May now, and my ear is still ringing — sometimes loudly enough to alarm me, but sometimes ever so quietly. There’s no predicting or controlling it. In any case, it’s a constant, bittersweet reminder that nothing is promised, that meeting my basic needs is enough, that anything joyful or comfortable or easy is a blessing, that plans and goals are pretty but unreliable. The things I do with my time now are more intentional, because they take more effort. But ultimately my time is still mine.

I start each day with a tour through the ecosystem around our house. I check the seedlings to see who’s thriving and whose stem has tilted in a misguided direction overnight. I look for any new blossoms and whether yesterday’s have disappeared to some other creature’s appetite. I notice new “weeds” in the lawn and look up on iNaturalist whether they’re likely to help or hurt. I check whether the blueberries are making fruit yet. I pull out the relentless new liriope blades that emerge every damn day. I make a note to take the weed whacker to the Virginia creeper where it’s getting out of hand. I always have dirt under my fingernails.

I visit Zora, the cherry tree I planted last fall, looking for any sign of life but knowing she’s as hopeless as she looks with all her leaf buds dried up, and I remember that life and death are not really under my control. I count the dozens of new redbud seedlings, also nitrogen-fixers, sprouting up everywhere. I watch for blooms of cosmos, nasturtium, larkspur, delphinium, milkweed, yarrow, and whatever else was in those wildflower seed mixes. I imagine the beautiful, lush, life-sustaining forest garden I could create and nurture on our little acre, with just ten more years to work on it.

And just like that, I find my dreams and thoughts germinating into pretty, unreliable plans once again, shooting fresh vibrant stalks and tendrils into the future as far as my mind’s eye can see. After all, I’m only human.

Recommendations:

I’ve learned a lot about soil and its role in our ecosystem from Gabe Brown, a North Dakota farmer and author of the memoir Dirt to Soil. Gabe also appears in last year’s documentary Kiss the Ground, currently available on Netflix.

John and I enjoyed “Modern Love,” an Amazon series based on the long-time New York Times feature of the same name. In one episode, Anne Hathaway gives a riveting performance as a high-achieving woman whose career and love life are thwarted over and over by her bipolar disorder, which she tries to hide. Watching it in the midst of my own mental health adventures, and wondering how they would affect my career and relationships, I felt very seen. But the whole series beautifully captures the precarity and preciousness of human relationships.

I reluctantly watched Sound of Metal, which was nominated for several Academy Awards this year. I was worried the film would feel too personal, being about a young-ish man who suddenly loses his hearing. And perhaps it did hit too close to home, but more because the movie was about loss in general than hearing loss in particular. Grief involves a tension between holding onto the person you were before the loss, and forging a new (and maybe even richer) identity as a person who goes on without what you lost. I know all too well what it’s like to be at that crossroads. If you do too, you’ll probably relate to this movie.

During my journey back to mental health, I managed to read Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, about the Great Migration of Black Americans from the South to the booming cities of the North and West. Their journeys were prompted by terror, undertaken with great risk, and often received with revulsion and violence. But without their brave pursuit of happiness in the country that called itself the land of the free, American culture today might be unrecognizable. It’s a must-read for anyone who wants a better understanding of why racial division in America is such an intractable problem.

Thank you so much for reading Evening Docket. This free newsletter is my way of processing what’s happening in our content-saturated era, and in my own life, and turning it into something that makes sense to me — although I do realize that I’m just creating more content. Still, I hope it helps you, too, somehow.

If you received this installment by email, please feel free to forward it to anyone else you think would enjoy reading it. To receive every installment, subscribe below! If you already subscribe, know how much I appreciate you, and please attempt to teach your email program that Evening Docket emails are not promotions or spam.

Dear Becki – I loved reading this, and I love you!! You are a beautiful human being. 💜

Your poem is beautiful as is your garden.